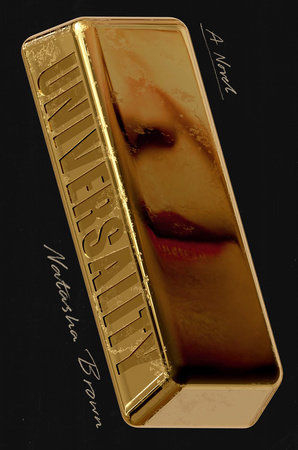

Universality by Natasha Brown

Forget Tiktok or generative AI. For my money the biggest challenge that has long face the novel is the rise of long form non-fiction. Do we need another Philip Roth when we have articles like “Who is the Bad Art Friend?” (reported by Robert Kolker in the New York Times Magazine). There are characters, plot, intrigue, and the merciless manipulation of the author, withholding and revealing the twists and turns, redirecting our sympathies with cool control. But most of all, real life grants that rare license for a kind of salacious melodrama we rarely see in the serious novels that are often preoccupied with confrontations of a far slighter variety.

It might seem like a logical step for a novel to appropriate the form, as Universality, by Natasha Brown, does in the first of its five chapters. The central event that the novel ostensibly concerns is delivered to us as a piece of long form journalism “Fool’s Gold” in the fictional UK magazine Alazon. There has been a crime: a young man lies in a coma after being hit across the head. But there are salacious details. He was hit across the with a gold bar, with a market value of half a million dollars. This gold bar was left lying around, forgotten about, by the wealthy financier Richard Spenser. A gold bar left lying around in his second home, a farm in Yorkshire that was overtaken by politically radical squatters, set on finding a better way to live by growing their own vegetables. It was the leader of this anti-capitalist group who suffered the cranial trauma from the bar of raw capital, which very much ticks the box for melodramatic details that you could never make up. But the most salacious detail of all in this plot, was that the assailant in this metaphorically burdened act, was the wastrel son of a prominent UK reactionary opinion writer. (Oh, and it happened during covid.)

The following four sections return to the familiar territory of the novel: the perspectives and interior lives of the various characters. We are introduced to Hannah, the journalist who wrote Fool’s Gold. She is a struggling journalist whose working class background held her back from making journalism into a career, and when covid hit she started working in a store to make ends meet. The article has been a singular professional success, bringing her some fame and fortune, but failed to provide the lasting profile or career break she was really craving. We then meet Richard Spencer, who was treated quite unfairly by the article that led to him being vilified in the public square. Then there is Miraim “Lenny” Leonard – the reactionary opinion writer of a type easily recognizable in the cursed pantheon of UK newspapers columnists. If the novel is truly interested in any of its characters, it is her. She is the mastermind behind the entire scandal – not the actaul assault itself, but rather in the subsequent furor. It was Lenny who fed the details of the story to Hannah in order to raise her own profile, just as she was transitioning to a more upmarket brand of newspaper and adjusting her political platform. Finally we meet Martin, a successful culture writer with the career that Hannah could only wish to have, who interviews Lenny onstage at Hay-like literary festival at the novel’s climax, hoping to achieve some kind of gotcha moment.

Unfortunately, Universality fails to deliver on its own literary devices, and suffers from its own contradictions. The opening section of faux-longform is a pale shadow of genuine long form journalism. The bar has been set very high – by the Americans, it has to be said. And as even Martin observes within the of the novel itself, Fool’s Gold isn’t a particularly good article. Are we to believe that Hannah has failed to succeed as a journalist because she is working class or because she is just bad at the job? She is certainly bad at the job, but then the novel leads us to believe that her more successful friends, Martin in particular, are little better. In this world, prestige jobs are sinecures held by the rich.

Universality is keen to make points about class in the UK, and very keen to be a novel about class. It is bewildering then how superficial its treatment of class in the UK is. The second chapter combines a dinner party hosted by Hannah, with flashbacks of Hannah’s life during lockdown. The passages that see Hannah abandoning her desperately held “cultural capital” as a journalist, and instead zoning out to Spotify at the end of the day after a shift at the store are the most interesting in the book, but the dinner party is a literary shambles, devoid of literary device, and falling back on characters regurgitating reactionary politics and barely constructed arguments. Judging by this novel, being upper class is now a mysterious thing that simply means you are wealthier, and have a far easier time finding work. It is true that class signifiers have become obscured, as Brown does observe, but there is a lot more to observe than the fact that some people go on expensive holidays. I found myself yearning for The Line of Beauty, Alan Hollinghurst’s 2004 Booker prize winner, an astoundingly well observed novel that captured a very particular era in English life.

It is one of the more tiresome features of modern intellectual life that we have to pay attention to the opinions fermenting in that bag of rotten apples that is the right wing. There is no avoiding the “intellectual dark web”, if we are going to understand the information and political landscape we are now navigating. It’s really terrible that this is the case because their ideas are bad and dangerous, but to top it off they are tedious as fuck. That, I think, Natasha Brown would be in agreement with me on. But the affection Brown finds for her antihero Lenny that at least earns her the final word feels bewilderingly unearned. The opinions are no less tedious and repulsive when Brown renders them. Then final confrontation, has Lenny expounding her tiresome politics, posturing cynically to a literary festival audience – who are inexplicably eating it up – as Martin makes desperate and pathetic attempts as her interviewer to skewer her.

Once again we are left with the challenge that the novel now faces to be relevant, and to deliver something that non-fiction cannot. If the novel’s climax had been recorded and put on youtube, I wouldn’t have even bothered watching it. I’m honestly asking myself what Brown thinks her own novel had amounted to by that point.